- Home

- Derek Mascarenhas

Coconut Dreams Page 18

Coconut Dreams Read online

Page 18

I watched Jim pour the concrete into one of the holes in the ground, but went inside when Joseph came back. I was scared of him. The rest of the day I only peeked out the window once: he was sitting under the tree in my spot again.

The next morning, the whine of an electric saw startled me awake. Jim and Joseph had returned.

After a strawberry Pop-Tart breakfast, I avoided the backyard and went across the street to call on my friends, Johnny and Pearl, but they were still away at their grandma’s. Mom was in her room working on her essay so I watched The Price Is Right. The contestant was wearing a Don’t Mess with Texas T-shirt. He didn’t listen to the audience shouting and overpriced his bid.

When I heard Mom in the kitchen I went to meet her. “Are you finished your essay?”

“Just a quick break.” She held a hefty mango in her hand, brought it to her nose, and said, “This is a good one.” Dad joked sometimes that she must have been a fruit fly in another life.

Mom glanced out the back window as she took out two plates and a knife. “Ally, why don’t you go outside? It’s so nice out. You should go play with Joseph, he’s probably bored.”

“It’s too hot. I was going to read inside.”

Mom held the knife over the mango like she was about to cut a birthday cake, then sliced along the seed. The flesh was bright orange. She’d given a mango to Pearl’s mom once but didn’t tell her how to cut it. Pearl told me her mom spent a few minutes trying to saw right through the seed before she gave up and threw it out.

Mom cut four large chunks of mango onto one plate, leaving the skin on. I got the seed, a slippery, tricky treat. I loved to scrape the juicy flesh from the seed with my front teeth and afterwards pick out the fibres stuck between them.

Mom ate two pieces, then gave me the plate. “Why don’t you go offer these to Jim and his son. Looks like they’re having lunch.” Before I could respond, she added, “Back to my essay,” and went upstairs.

My first thought was to just eat the remaining pieces, but Mom’s desk upstairs overlooked the backyard and she would know if I didn’t go.

I rinsed my hands under the tap for longer than normal. I was nervous about facing Joseph again and thought he might try to fight me. I went to the family room and, from the glass jar on the mantel that had my seashells, I found the one Dad had given me. It stood beside his old slingshot that we weren’t allowed to use, though he promised he’d teach us one day. Dad had brought the slingshot and the shell with him when he first came to Canada. When he gave me the shell he said it was from Baga Beach, near his old home. He told me he wanted to bring part of the ocean with him. I hadn’t seen the ocean yet—the closest thing we had nearby was a lake that we couldn’t swim in. I put the shell in my pocket and went outside with the plate.

I could smell the sawdust and wood chips that littered the grass. The deck was beginning to take shape; I was careful to step over the frame as I carried the mango out. Jim and Joseph were sitting on a stack of lumber.

“My mom asked me to check if you wanted some mango.”

“Sure,” Jim said. “But only if you take some cheese in exchange.” He held out a Babybel wrapped in red wax.

I agreed, and they each took a slice of mango from the plate. I peeled the wax from the cheese and ate it in three bites. Then I rolled the wax into a ball, took out my shell, and pressed the wax onto its outside.

“Delicious. Thank you, Ally.” Jim placed the mango skin back on the plate.

I looked at Joseph to see if he was done but didn’t see his mango skin. He had an embarrassed look on his face and said, “I didn’t know you weren’t supposed to eat the skin.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “Some people eat the skin, too.”

“What’s that you have in your hand?” Jim asked me.

“It’s a shell my dad gave me. If you put it to your ear you can hear the ocean. A girl in my class said it’s only your blood moving that makes the noise, but I don’t think so.”

“Can I see, please?” Joseph said. I was surprised he asked so nicely, and when he took the shell I felt the roughness of his fingertips on the palm of my hand for just a second.

“Back to work for me.” Jim packed up his lunch and returned to measuring lengths of wood around the frame.

Joseph held the shell up to one ear, then the other. “I hear it, but what’s that other water sound?”

“Oh, that’s our next-door neighbour’s pond. Mr. Fanning. There used to be fish in the pond but the racoons ate them—he swore so much that morning. He’s kind of mean. When our tennis balls go over his fence, he doesn’t let us go get them.” I paused. “Do you hear the wind chimes?”

Joseph nodded.

“Those are Mrs. Gardner’s. Our neighbour on the other side. She’s nicer.”

“Do you hear that whistling?” he asked. “That’s my dad.”

Joseph had one crooked tooth like his dad, and an even wider smile.

Jim was whistling a song I recognized but couldn’t remember the words to. His hammering seemed to keep time with the tune. He was so quick, as if the hammer were a part of his arm. Two taps to hold the nail in place and two harder ones to drive it clean into the wood.

Joseph and I listened as the hammer and whistle blended with the other backyard sounds. Then I realized we were both just standing there, and I got nervous and started to talk again.

“Mrs. Gardner gave us that honeysuckle plant over there. Do you want to try one?”

I picked the thin flower and sucked the sweet drop of nectar from its base.

Joseph handed back my shell and did the same with another flower.

I felt a sneeze coming on again. My head tilted back, but I put my finger under my nose, like a moustache, and stopped it.

Just then Joseph let out a big “Ha-choo!” It was as if he’d stolen my sneeze. We looked at each other and laughed.

A monarch butterfly landed on one of the honeysuckle flowers. Joseph slowly brought both hands up and around the monarch. I thought he was going to kill it, until I saw how delicately he held its orange, black, and white spotted wings.

“If you hold them too tight you’ll crush them. Too loose and they’ll fly away.”

He brought the butterfly to his mouth and started whispering. He lowered it, and then held it up to my face. “Make a wish.”

“Why?”

“Just whisper a wish, and it’ll come true. Butterflies can’t make any sound. They can’t tell anyone your secret. It’s true, my mom told me.”

Joseph seemed really proud of this, so I leaned in. I couldn’t think of a good wish so I asked for a million more wishes in a whisper too quiet for him to hear. Joseph whispered as well but took longer to make his wish—I had a feeling it was for something real. He let the butterfly go, and it fluttered away.

On the third day, the sound of hammering woke me with less of a scare. I had dreamt of the ocean. I was a fish, swimming with many others. When I tried to swim free, going whichever way I wanted, I got separated from the school. I wandered the ocean, trying to find those like me, except I woke up before I found anyone. My dream catcher must not have been working. I wondered if Joseph believed in them, after what he’d shared about butterflies.

That morning, I had to go grocery shopping with Mom. By the time we got back and put everything away, it was afternoon.

The deck looked like a deck now, yet my first steps onto it were cautious.

“Almost done,” Jim said to me from the other side, where he was working on the stairs. “It’s safe. Go on, jump as hard as you can.”

I did a little hop first, but when I felt how sturdy it was, I jumped twice, full strength.

“Attagirl.” He stood up and turned to Joseph, who was sitting on the grass next to the toolbox and a loose pile of wood. “Just gotta run to the hardware store. I’ll be back in a flash.”

>

Joseph nodded. I walked over and sat beside him on the grass. He had a magnifying glass in his hand and directed the sun to a point on the rubber sole of his shoe. I saw no smoke, yet there was a funky smell in the air.

He reached over to the pile of wood and pulled a long piece in front of him. Raising the magnifying glass, he started to burn dark lines into the light wood grain with the sun’s rays. I stayed quiet as he drew. A shape started to appear—a shell. And beside it, the outline of a butterfly.

When he finished, all I could do was stare. I’d never been given a gift like that. I didn’t know what to say, and so I said the first thing I could think of: “I’m thirsty.”

“I’ll go turn on the water.” Joseph ran to the side of the house.

The hose, coiled in the grass like a snake, came alive. I held it and drank.

Joseph came back and I handed him the hose. He held it vertically like his father. I couldn’t resist bending the hose into a kink. He leaned in and looked right into the spout just as I let my grip loosen. Water gushed into his face. He covered his eye with both hands. I moved closer to see if he was okay, but caught the smile forming in his cheeks too late. He put his thumb to the spout and sprayed me from head to toe. I let out a scream and tried to wrestle the hose away from him. Our laughter joined the other backyard noises as water flew in all directions.

Jim finished the stairs that afternoon. “Let your mom know there’s just the railing to do tomorrow,” he told me. “Should only take a couple hours.”

As Jim packed up for the day, I realized we hadn’t saved the piece of wood with the burned-in drawing. I told Joseph, and he said he’d help me find it tomorrow. I wanted to give him a hug goodbye but thought his dad or my mom might see me and I chickened out. Instead, I waved goodbye to him, even though I was right beside him. He waved back, and I went inside. Everything seemed darker as my eyes adjusted. It reminded me of coming out of a movie theatre during the day—your eyes go from dark to light instead, but it was the same feeling. Sometimes, if the movie is really good, you’re not ready to go back to the world you knew.

I got excited the next morning when I heard the hammering from the backyard. It was the last day Joseph would be coming, and I wanted it to be special. I braided my hair and put on my favourite pair of jean shorts. Mom never wore perfume—I looked for some in her room but didn’t find any. I settled for a perfume sample in an old copy of Chatelaine that Pearl had given me. I rubbed the page on my neck, and from my shell collection I picked out one I’d found at Sauble Beach to give to Joseph. It was shaped like a mini ice cream cone with a hole at the top.

When I went outside, Jim was putting up the railing, but I didn’t see Joseph anywhere.

“Where’s Joseph?” I asked.

“Oh, his mother came and took him.”

I waited for Jim to say more, but he directed his attention back to his work.

Back inside, I kept pressing the shell’s point into my thumb as I looked out into the backyard. My spot under the maple tree was empty. I went to put the shell back in the glass jar, but instead took my dad’s slingshot, put the shell in, and fired it against our couch. It just bounced off the floral orange cushions. I put the slingshot back so I wouldn’t get caught.

Jim completed the railing in an hour. Mom finished her essay that morning, too. She told Jim he’d done an excellent job and wrote him a cheque.

As he folded the cheque and slid it into his pocket, I asked, “We need painting done, too, can you do it?”

Jim said he did paint, too. Mom told him we might be in touch, and he thanked her again, then packed up the last of his tools and drove away.

Mom took a couple of weeks to call Jim, and when she did, the number was disconnected. It was a scary feeling to realize how easily people can enter and exit our lives.

When I found Joseph’s message at the end of the summer, I was practising with the slingshot. Dad had finally taught me how to use it. I had to use a rubber ball and shoot away from the house, but I was getting good at knocking empty cans off the railing. After hitting two of the three cans I’d set up, I went to fetch them and noticed something on the underside of the railing. It was the drawing Joseph had made with the magnifying glass. There was a shell, a butterfly, and a heart in between. My first love letter, written with the sun, now hidden in a place the sun couldn’t reach.

We moved from that house a few years later. By then, Mom had found a teaching job. The banker forcing us from our house never materialized, and yet we still left sooner than any of us expected. Mom got pregnant with my baby brother, Eric, and our house became too small.

My maple tree lost its leaves early the year we moved. Dad said, “It knows we’re leaving.” He told me that the year he moved to Canada, a mango tree on the family property stopped giving fruit. All life left the tree and it stood like a stone for years before it was eventually brought down by the monsoon rains.

I made sure to say goodbye to my tree before we left. I sat in my spot and held my hand against its roots for a long while. I wished we could have taken it with us. I’d wanted to take the section of deck railing where Joseph’s drawing was, too, but that meant I would have had to tell someone else it was there. I’d gotten a camera for my previous birthday and later I couldn’t believe I didn’t think to take a picture of it before we moved. When I looked at it that last time, like every time before, I wondered where Joseph was. I remember learning that summer just how delicate love could be.

Our neighbourhood friends, Pearl and Johnny, had told us that after we left, the people who moved into our house changed everything. They ripped up the deck and put in a stone patio. Even though it was their house, I resented them for it. That feeling faded as our new house became our new home. Somewhere between house and home, I grew up. I went to high school. And after high school I left for college in Toronto.

The autumn air is cool as I walk toward OCAD for my photographic history class. I hold a warm tea in my hands and pass students on the sidewalk wearing scarves and jogging pants with U of T printed in white on their bums.

I’m early and take my time to admire Beverley Street’s deep yellow-and-crimson foliage, and the large houses of weathered brick. My apartment is in the basement of one such house farther north on St. George. I’m lucky to have an apartment to myself, but the couple upstairs get into intense shouting matches and sing together when they make up. I put on headphones or go for a walk. Since I moved in September, I haven’t ventured too far or often outside my neighbourhood, and when I do, I draw little maps on crumpled pieces of paper so I don’t get lost. The city still feels huge compared to home.

Before I reach Grange Park, I stop at a wooden telephone pole. There are layers of posters stapled to it—the top one is for a show by a band named Wine Jacket. The wood looks scarred by the staples driven on top of each other, rusted and black. I place my tea on the concrete next to my sneakers while I take the cap off my camera and snap a photo.

I find a bench in the park and sit and sip my tea. Mom’s habit of sitting outside with a cup of tea has made its way to me. If only her culinary skills had as well. Mom packs me a couple of small containers of chicken curry to take home when I visit, which I usually end up eating my first day back at school. When Mom calls, she asks what I’ve eaten, while Eric and Dad ask when I’m coming home next. Each time I go home for a visit, I tell myself I make the journey for my parents’ and brother’s benefit, but, honestly, I miss the chaos, the jokes, the fights, and the closeness that only those called family share. I’d made a few friends in class, and love the variety of people and anonymity the city provides, and yet I still feel lonely walking back to my place.

I drink the last gulp of tea, sweeter than the rest, and pull out Aiden’s postcard from India. He addressed it to Ally-cat and drew a small claw beside it. I laugh again when I read, Despite my life being dictated by bowel movements, the food is unreal.

He talks about our family there, and how there are So. Many. People. He asks how everything’s going on my end and signs it with love, and, P.S. Ally, this place changes everything. You have to come. After I finish school, I will.

I notice a black squirrel nearby vigorously digging a hole in the grass. He moves a few yards over and starts to dig again. I wonder how many trees grow from the nuts that squirrels bury and forget about.

A larger grey squirrel approaches the first one and a chase begins. I follow their zigzags with my eyes until they both dart up a tree to my right. Then I notice the maple tree next to the one they ran up. Well, not so much the tree, but the young man sitting against its trunk. He has long dark hair and his bare knees stick through two frayed holes in his faded black jeans. The way he’s hunched over his notebook looks oddly familiar. I tell myself it’s likely someone else, but a feeling in my stomach urges me to investigate.

I walk to a garbage bin that’s beyond where he sits, but don’t pass by close enough to catch a glimpse of his face. I toss my cup in the garbage and loop back, this time coming straight up behind him.

As I approach him, my steps are careful. My heart pounding.

I’m close enough to see over his shoulder now; what I see on the page is the city coming alive as I’ve never seen it before. His hands look dry, and his left holds a pencil that makes quick and crisp lines blending into gentle shades. The scene looks like a dream. Or maybe a memory.

Then I notice the point of the pencil in his hand—the edges and tip are flat, like they were sharpened with a knife.

2006

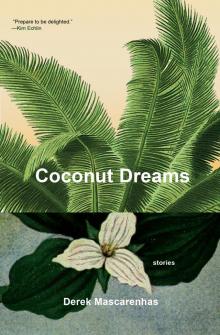

Coconut Dreams

Four days in Goa nearly killed me. It started the morning my bus arrived in Mapusa and I couldn’t find my uncle Quinton. A swarm of rickshaw drivers crowded me as I tried to dig my bag from the cavity of the bus. “My uncle is picking me up,” I repeated, heaving my backpack onto my shoulders. Less than a week before Christmas, the morning sun was scorching. I pulled my cell phone from my backpack—one bar of battery power—and found my uncle’s number.

Coconut Dreams

Coconut Dreams