- Home

- Derek Mascarenhas

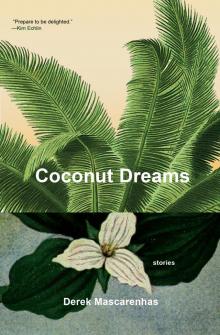

Coconut Dreams Page 3

Coconut Dreams Read online

Page 3

Felix refused to speak to them. He didn’t want to admit he’d heard the same thing. He didn’t want to tell them what he’d seen either, as he wasn’t sure himself—the fire, the figures. And how they’d just vanished.

The thought that he might indeed be cursed entered Felix’s mind as Father Constantine introduced Father Salvador. The shorter members of the congregation and those in the back stood on their tiptoes to catch a better glimpse of the new priest stepping up to the pulpit. Having already met him, Felix let his Nunna have the better view, but she sat back down soon after, rubbing her knee.

Father Salvador thanked Father Constantine and turned to address the congregation. “I’m already overwhelmed by all of the pious people I’ve met and look forward to becoming part of this community. I’m also thrilled to be able to assist Father Constantine and learn from such a fine and long-standing servant of our Lord.”

Felix’s Nunna exchanged smiles with her friends, impressed by Father Salvador’s respectful demeanour. The new priest stood silently at Father Constantine’s side as the older priest conducted the mass, but when the time came for the sermon, he delivered a passionate call to help the less fortunate: “If we cannot help our fellow people, what other purpose do we have in this life? Especially on this day celebrating St. Francis of Assisi and his good deeds.”

To the congregation, it was like a fresh light after years of the same dull words without action. But for Felix, he connected most with Father Salvador’s childhood: “I was but an orphan on the streets, never knowing my mother or father, and losing every person who cared for me. But God took pity on me and showed me the light. The Church took me in. Saved me.”

After the mass had ended, the fair began outside. Violinists and accordion players performed their old Konkani songs, with some of the crowd singing along, and stalls sold sweets and small toys. Despite what had happened the night before, Felix’s father, perhaps feeling guilty for using the cane, gave his three boys money to spend. Felix found Clara, and with his father’s money, bought them the kadio bodio they had been craving, along with the sugar-filled and snowflake-shaped fulfuli. They ate their snacks watching Wagh Marea—who normally only visited the church for confession—secretly freshen his sugar-cane juice from the stand with a liberal splash of fenny.

A crowd had gathered around Father Salvador, and Miguel soon called Felix and his brothers over to their Nunna, who held her knee. He told them she was in pain and needed help home. Felix was going to volunteer to take her, but his father told Nicholas and Jacob to go.

“But the fair just started,” Nicholas said.

“And why does Felix get to stay?” Jacob asked.

“Because I said so. You can both come back after. Now go.”

As they walked away, Miguel gestured to Felix to join the line to meet Father Salvador; Felix knew his father had chosen him only because he’d already met the priest, but he couldn’t help but feel more special than his brothers.

Meanwhile, Diego had joined the celebration, avoiding Wagh and tying his horse not far from Father Salvador’s carriage and horse beside the church. The crowd parted to let Diego skip the line to meet Father Salvador, though he shook his countryman’s hand for longer than normal and held his eyes inquisitively—almost suspiciously. Felix assumed that Diego was jealous of Father Salvador getting the attention he normally received.

The line inched forward, and Felix and Miguel finally had their turn.

“Felix, how are you? This is your father, I assume?”

“Yes.” Felix was surprised that Father Salvador remembered his name, and he looked up at his father to ensure that he’d noticed, too.

“Pleased to make your acquaintance,” Father Salvador said, and shook hands with Miguel. “Your son was so kind to point me in the direction of the church yesterday.”

The priest offered Miguel a cigarette from his pack and lit it with his silver lighter, and then asked Felix what he planned to do the rest of the day.

Miguel answered for him, “Hopefully not get into more trouble.”

Felix looked at Father Salvador, embarrassed by his father’s words. But the priest only laughed. “He couldn’t have gotten into that much trouble.”

“He spends too much time under the zamblam trees. What do you think about those trees? They say they’re haunted.”

“Oh, that’s just rubbish.”

Felix grinned, delighted the priest had taken his side.

Father Salvador continued: “As long as you have faith in our Heavenly Father, you should not worry about such things.”

Miguel pressed further. “But has Father Constantine told you about the house at the top of the hill yet? The boy went there last night as well.”

“That’s another story. Felix, you must not go looking for evil.” Father Salvador’s tone turned severe and he put a hand on the boy’s shoulder. “You must promise me not to go to this house again.”

Felix was confused why he would say one superstition was nonsense and the other not, though he wanted to remain on Father’s good side. But before Felix could promise, a horse neighed loudly nearby, interrupting them. They turned to see Father Salvador’s horse stomping its feet and tugging at its tether. It had an erection and was staring at Diego’s horse.

All eyes were drawn to the horse’s rigid penis, engorged to the size of a man’s arm.

“Bastard!” Father Salvador shouted, and rushed over to take the reins and direct the horse away.

People laughed, and Wagh Marea was quick to quip, “Someone forgot to tell the priest’s horse he’s supposed to be celibate.”

Felix had never heard a priest swear before but was glad the distraction freed him from his father further embarrassing him. He slipped away and walked home alone.

In just a few short days, Father Salvador made an impression on the village, and the incident with the horse was overlooked. He visited families and offered his advice to anyone who asked. “Such a lovely young fellow,” the older women said to each other. “Straight from God he was sent,” others said, which might have had something to do with the fact that he had doubled the collection-plate money on the feast day.

By the following Sunday, it felt as though Father Salvador had been living in the community for years. That Sunday was also the anniversary of Felix’s mother’s death. Although Felix’s family celebrated his birthday the following day, his actual day of birth had always been spent at home in mourning. Their only excursion was to attend mass, dressed entirely in black.

At mass, Clara and her family offered condolences to Felix and his. Felix hadn’t felt the day’s sadness until he saw Clara, as if seeing his close friend made him aware of what he had lost. When Clara hugged him and said, “I’m sorry for your loss,” he thanked her and squeezed her tighter and longer than the rest of her family.

When it came time for Father Salvador’s second sermon, the parishioners hushed one another and leaned forward in their seats.

“One day, just before mass, a young priest couldn’t find the sermon he had prepared. He frantically looked through all of the drawers of his desk and dresser without any luck.”

Felix enjoyed how Father Salvador brought the story to life by opening imaginary drawers.

Father continued: “The priest finally turned his head skyward, closed his eyes, and prayed to our Heavenly Father. He said, ‘God, if you help me find my sermon, I swear to give up whisky for the rest of my life.’ The young priest opened his eyes, looked down, and saw the sermon lying right in front of him on the dresser.” Father Salvador paused to capture the parishioners’ full engagement. “The young priest looked skyward and said to God, ‘Never mind, I found it myself.’”

The congregation erupted in laughter. Felix couldn’t remember a time he’d laughed like that in church. Though his father was not laughing: his jaw was clenched, his eyebrows furrowed in rage.

> Back at home, as they had every year, Felix’s family kept a vigil by the altar in their main room, with a single photo of his mother on display amid the lit candles and fresh garlands. They fasted during the day, and Felix’s stomach grumbled as they worked their way through the rosary. But he welcomed this hunger, as if he deserved the discomfort and slight pain for having had any part in taking his mother away.

While his father and Nunna closed their eyes during the prayers, Felix caught his brothers playing tic-tac-toe. He tried to think loving thoughts of his mother, but the repetition of the prayers made it feel so impersonal. His father never shared any special stories or details about his mother—all they had was that one photo of her as a teenager, her shoulder-length hair parted down the middle. In the flickering candlelight, Felix stared at it now. His mother wasn’t smiling but looked like she was about to. If only the picture had been taken a moment later.

As the evening angelus church bells rang, they ate only dal and rice for supper. Jacob and Nicholas licked their fingers, and Felix’s Nunna said, “Hunger makes the best curry.”

After the meal, Miguel went to place a glass bottle of holy water next to the picture on the altar, but realized he’d forgotten to have Father Salvador bless it.

Felix jumped at the chance to escape and volunteered to take it to the church. He fetched Clara, and together they made their way to the church in the waning light. As they neared the statue of St. Francis of Assisi, they heard the church bells ring out in rapid succession.

“Something must be wrong,” Clara said, recognizing the call for help.

“Let’s go check,” said Felix.

They discovered Wagh Marea sitting on the church steps, rubbing his head. But before he could tell them what had happened, a rumble of horses approached from the village. Diego and a few other men on horseback galloped to the church entrance, kicking up a trail of red dust behind them. The riders came to a halt, and the dust clouded Felix’s vision for a few moments.

Diego asked, “What happened?”

“Robbers,” Wagh said.

Diego waited a few seconds, unaccustomed to such a short reply from Wagh. “What did they take?”

“They took Father Salvador and his horse and carriage and rode off. Raided the church, too. Took all the money from the collection, and as much gold and silver as they could carry. They tied up Father Constantine and the bell operator inside. I had to untie them.”

“How many were there?” Diego asked.

“Just two. One fellow was big as a bear, though; the other one thin but strong.” Wagh rubbed his swollen head. “And they took my bottle of fenny, too, and gave me a knock on the head with it. Bastards. It was a full bottle!”

“I don’t care about your bottle, Wagh. Which way did they go?”

“The road down by the river.”

“And you say they rode Father Salvador’s carriage?”

“Yes. They came in on one horse but stole Father Salvador’s horse and carriage with him inside.”

Diego talked with his fellow riders and told Wagh to stay at the church, then turned to Felix and Clara. “Go home. This isn’t the time for children to be out,” he said, before riding off with the others down the road by the river.

As Felix and Clara walked away from the church, Wagh’s description of the robbers resonated in Felix’s mind: one big, one thin. He grabbed Clara’s shoulder and said, “I think I know where they’re going.”

“Who?”

“The robbers—I saw them behind the house at the top of the hill. We have to help Father Salvador.”

Moonlight shone over the vine-covered house and the expansive zamblam tree as Felix and Clara approached, slightly out of breath after climbing the hill. Along the way, Felix had pocketed stones for his slingshot, switching the bottle of holy water from one hand to the other.

The stone that Felix’s brothers had used to block the front door was still there, and Clara found the dropped flashlight and tested it. The beam illuminated a man striding toward them from the hill path.

“Felix!” cried this figure—Miguel. “What are you doing here? As soon as I heard the bells I knew I shouldn’t have let you out. I sent your brothers to the church, but something told me I’d find you here. You haven’t learned your lesson. And worse, you’ve brought Clara again.”

“There’s been a robbery at the church, and I saw the robbers here the other night. And they’ve kidnapped Father Salvador.”

Felix watched his father’s face change briefly from anger to concern, but then Miguel glanced up at the old house, staring at it as if it had just appeared. Then he noticed the giant zamblam tree he’d hurried right past. “We need to get away from this cursed place,” he said, his voice trembling. “God will take care of the priest.”

But it was too late—the horses and carriage came thundering onto the property. The slender man dismounted from the lead horse, and the bear-sized man and Father Salvador hopped down from the carriage. The priest wasn’t tied up. In fact, he carried a rifle, which hung over his shoulder instead of being pointed at the pair of robbers.

Clara grabbed Felix’s hand and squeezed. In her other hand she accidentally flicked the flashlight off, then clutched it to her chest and looked up at the men.

“What have we got here?” asked the bigger man, who had the thickest arms Felix had ever seen.

The skinny man shook Wagh’s bottle of fenny at Miguel. “You chose the wrong night to come here.”

Led by Father Salvador, the trio of robbers approached.

“God will protect us,” Miguel whispered to no one in particular.

Father Salvador stood before Felix. “Does anyone know you’re here, son?”

“Diego is on his way,” Felix tried, but his shaking voice betrayed him.

Father Salvador took out a cigarette and lit it with his silver lighter. “Ah, but they’ve gone chasing us in the complete opposite direction.” He drew a long puff and exhaled. “Now, the question is, what can we do about this situation?”

“God will protect us,” Miguel repeated.

Father Salvador turned to the massive man. “Ox?”

“Up to you, boss,” he said.

“Gustavo?”

The skinny man laughed, then opened the bottle of alcohol. He took a swig and coughed. “Whoa, that’s strong!”

“How could you?” Clara spoke up to Salvador, surprising Felix. “Pretending to be a priest. You’re a disgrace!”

“I may have presented myself in a certain manner,” Salvador said. “But everyone in the village made a choice to believe me. I think the smaller the village, the more it needs to believe that some people are closer to God than others. Simply so they have a scale on which to place themselves. Now, what’s more disgraceful?”

Salvador took a final drag of his cigarette and exhaled the smoke in one long plume. He ground out the cigarette with his foot, walked over to Felix, and removed the bottle of holy water from his hands. Felix watched helplessly as Salvador opened the cap of holy water and drank the bottle empty.

Miguel repeated, “God will protect us.”

Felix clenched his fists. “Stop saying that!” He stared at Salvador with contempt and touched the pocket that held his slingshot. But, glancing at the rifle again, he didn’t reach for it.

Salvador wiped his mouth, said, “It’s just water,” and tossed the empty bottle to the ground. Then he walked over to Gustavo and took the bottle of fenny. “And this is just alcohol.” He gave it a sniff but didn’t drink it. “Now, unfortunately we can’t let you three go and tell my secret to the world.” Salvador walked up to the house and began splashing the alcohol on the dry vines covering the outside walls. When it was empty, he threw the bottle on the roof, where it shattered. Then he motioned to his partners. “Put them in the house.”

Gustavo took the flashlight fro

m Clara and tossed it to the ground. He grabbed Felix and Clara by the arms and brought them to the door. Ox handled Miguel as easily as his accomplice did the children, and with one hand moved the stone away from the door so they could push their captives inside.

The closing door brought darkness upon them.

“I told you not to come here,” said Miguel. But he sounded feeble now.

Felix tried to open the door, but Ox had rolled the stone back in place and it wouldn’t budge. In the dark, he found Clara’s hand and they pulled each other close.

“Oh, Rosetta, why did you leave me?” Felix’s father cried.

From outside came a crackling sound.

“They’re lighting the house on fire!” Clara shouted.

But Felix’s father only continued. “I knew this child would be the death of me. It wasn’t enough he took you away from me.”

Felix could smell smoke. Seething, he shouted back at his dad, “It’s not my fault Mom died!”

The flames were devouring the dry vines that covered the house. The whooshes and crackles of the fire grew louder and the spaces between the tiles glowed. But down the hallway, through the back kitchen, shone a different kind of paler light. Moonlight.

Still holding Clara’s hand, Felix told her, “I know a way out.”

Felix’s father again cried, “Rosetta!”

Felix took two steps down the hallway but turned back. He found his father’s hand and pulled him to his feet. They ran toward the backroom. The old roof tiles rattled and began to crack and fall, shattering on the floor around them.

Felix jumped out the window first, then helped Clara out. His father stood there, framed in the window of the burning house. For a moment Felix wondered if he didn’t want to be rescued.

Coconut Dreams

Coconut Dreams